Small glaciers at relatively low latitudes can act like highly sensitive climate “thermometers”, responding quickly to changes in temperature and precipitation. They also serve as natural archives, preserving evidence such as glacial deposits that help scientists reconstruct past climate behaviour.

Beyond the scientific loss, disappearing ice can increase geological risks. As long-frozen ground (permafrost) thaws, rock faces can become less stable—raising the risk of rockfalls that threaten hiking routes, shelters and visitors in mountain national parks.

Professor Santos González described a deeper sense of loss too—an erosion of identity and memory tied to the landscape—what researchers call “landscape mourning”, as a familiar element of the mountains disappears for good.

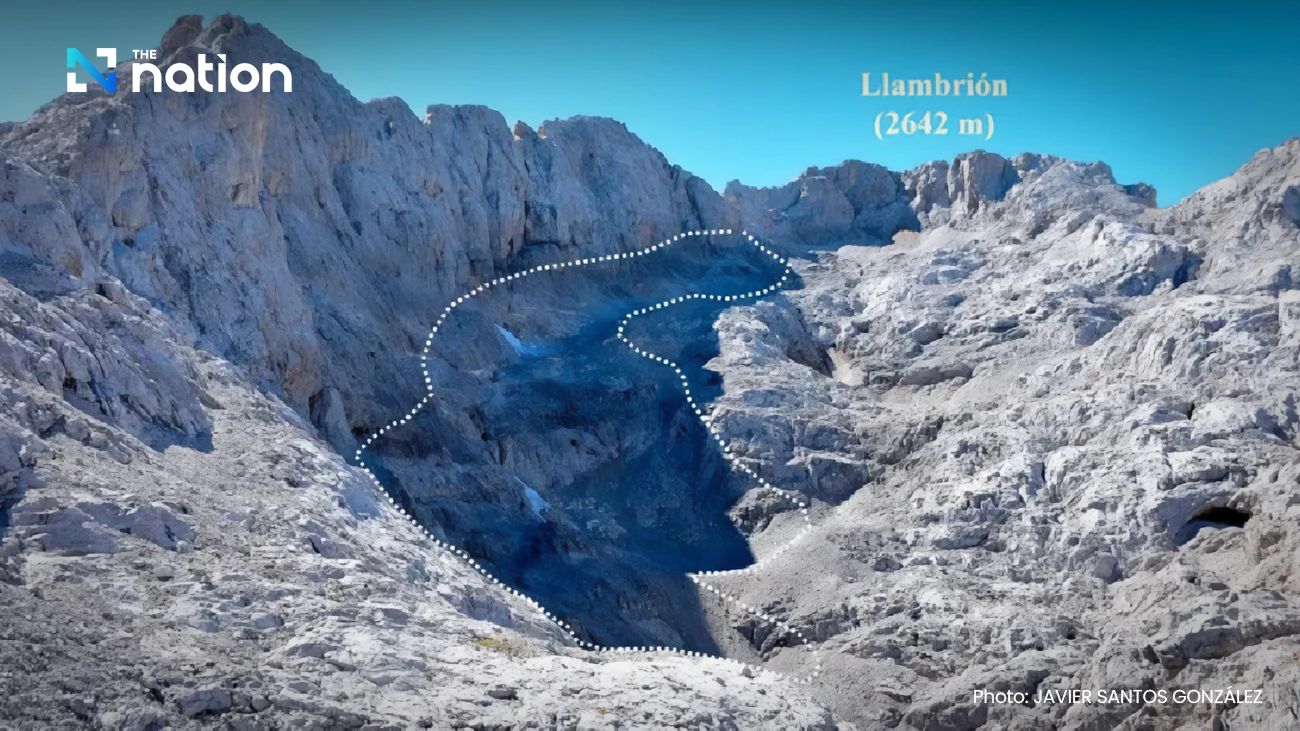

Trasllambrión’s fate is increasingly reflected elsewhere in Spain and southern Europe. In the Pyrenees, where glaciers have been shrinking rapidly, scientists note that the number of active glaciers has fallen sharply—from around 52 in the late 19th century to roughly 14 today.

One of the most closely watched is Aneto, often cited as Spain’s largest glacier, which has been losing substantial ice each season. Studies using LiDAR and drone surveys warn that, if current warming trends continue, most of Spain’s remaining ice could largely disappear within the next decade.