When the high-speed rail line between Barcelona and Madrid opened in 2008, hundreds of thousands of people ditched the plane in favor of the train, helping significantly lower carbon dioxide emissions in the country. Progress elsewhere in Europe has been slow. But with the European Commission’s new plan to accelerate the development of high-speed rail in Europe, the continent’s travel emissions could plummet.

—

It is a well-known fact that short-haul and domestic flights are the most polluting forms of travel. Despite this, European governments have long subsidised and invested in air travel over rail travel, resulting in today’s norms of continental travel being very plane-centric.

In 2016, the European Union announced the Fourth Railway Package, a set of legislation aimed at “revitalising the rail sector and making it more competitive vis-à-vis other modes of transport.” While this package did not directly fund any infrastructure or route developments, nor subsidies for the rail industry, it removed a lot of the red tape that had historically held back rail development, creating a legislative environment more conducive to a competitive rail industry and paving the way for more concrete initiatives and investment.

Last month, the European Commission announced a comprehensive plan to accelerate the development of high-speed rail in Europe through greater coordination and streamlining of ticketing, timetabling, funding, operations and legislation. The plan aims to deliver a continent-wide high-speed rail network by 2040. This will be achieved through a series of actions, including improving funding sources and private investment coordination as well as cross-border rail ticketing and booking systems; simplifying train driver certification, and removing redundant national rules.

The project is also expected to significantly reduce the EU’s transport-related emissions, supporting its goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. Spain’s high-speed rail impacts on CO2 emissions are a good example to illustrate the potentially huge impact that an Europe-wide initiative could have.

Case Study: Spain

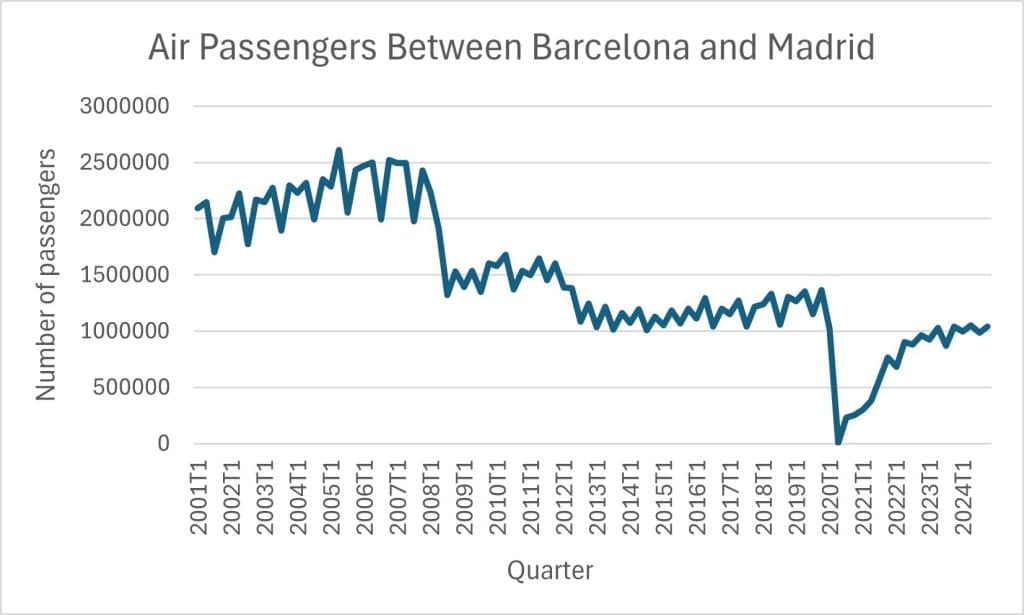

In 2008, a new high-speed rail line opened between Barcelona and Madrid, cutting the journey time between the two cities by train from around nine to two-and-a-half hours. Almost instantly, air passenger numbers declined.

Data from Eurostat shows a reduction of roughly one million passengers per quarter – or 40% – immediately after the high-speed line was opened in February 2008, rising to around 60% by 2024. The Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia (CNMC) – Spain’s independent competition regulator – has been only collecting data on passenger numbers since 2016.

A 2005 study at Oxford University calculated that around 153 grams of CO2 is emitted per passenger kilometer on short-haul flights. This means that every passenger that flies the 481-kilometer stretch between Barcelona and Madrid airports emits roughly 74,000 grams of CO2.

As for high-speed rail, the UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and the French public train company SNCF estimate four and three-and-a-half grams of CO2 per passenger kilometer, respectively. The high-speed line between Barcelona and Madrid is 681 kilometers long, meaning every passenger emits around 2,550 grams of CO2.

The Results

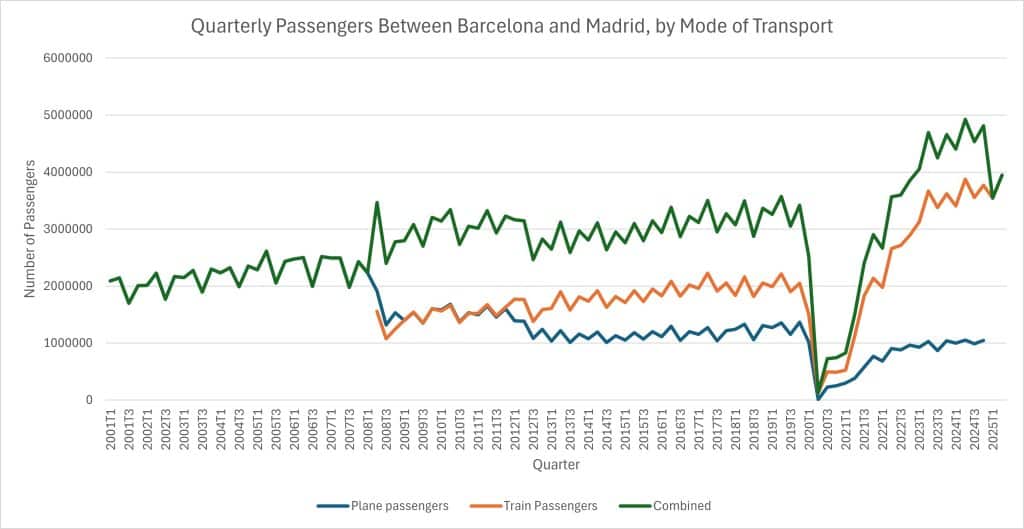

Using the passenger figures from Eurostat and CNMC, we can draw a graph that shows the number of passengers by mode of transport over time. As we can see, the total number of passengers between Barcelona and Madrid wasn’t hugely affected, as the new train route took on the passengers that were no longer choosing to fly. This shows that peoples’ ability to travel between these cities was not affected – only they now had an alternative, which quickly became the preferred mode of transport.

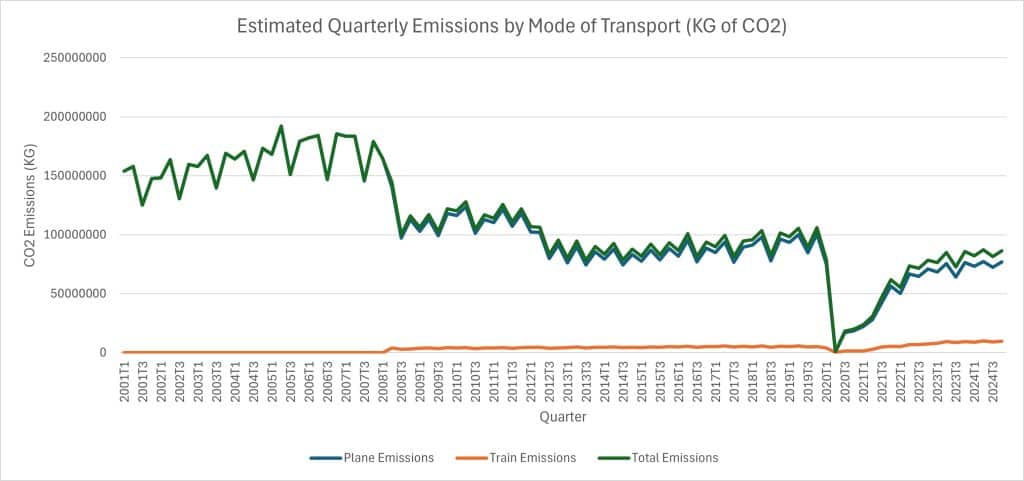

But what is really striking about these figures can be seen when we apply our estimates for the amount of CO2 emissions per passenger. These estimates allow us to compare the CO2 emissions over time of air travel and train travel between Barcelona and Madrid.

Here we can plainly see just how much greener high-speed rail is than air travel. Even though the number of train passengers was higher than plane passengers from around 2012 onwards, rail emissions pale in comparison to the emissions from air travel. Had the high-speed line never been built, CO2 emissions from this route would be three times as great in 2024.

As more people opt to take the train instead of a flight, as has been the case since the pandemic, CO2 savings grow. In the second quarter of 2024, the actual total emissions were 275 million kilograms lower than if all passengers had flown, which is roughly equivalent to the emissions of over 183,000 British households over the same time period.

Learnings for Europe

The European Commission’s newly announced plan targets a number of routes. Some of the biggest improvements include reducing the Copenhagen–Berlin route from seven to four hours; Berlin–Vienna from over eight hours to four and a half; and Sofia–Athens from nearly 14 hours to just six. Additionally, the plan would create new routes, between Paris, Madrid and Lisbon, and between the Baltic states and Warsaw.

No doubt, the improvement, or opening, of high-speed rail routes across Europe will present an alternative to flying as a means to travel between two cities, and as a result will take passengers off planes and put them onto trains instead, lowering the overall emissions. As the Barcelona–Madrid route shows, this can have a stunning impact – across 2024, around one million fewer tonnes of CO2 were emitted than if the high-speed line had never been built, which is more than the total annual CO2 emissions produced by the Faroe Islands, Gambia or French Polynesia.

It is difficult to estimate exactly how large the impact could be on any given route. The corridor examined here was very successful, and a 60% reduction in air passengers is not to be taken for granted. Nevertheless, it is clear that investment in railways as an alternative to air travel has the potential to have a hugely positive environmental impact, and the EC’s plan must prioritize maximizing passengers in order to make this impact as big as possible. The key to this will be through affordable tickets, fast and reliable journeys and reduced red-tape, and it’s vital that the EC recognises this. It’s high time that countries begin to offer the same, if not greater, legislative benefits that the aviation industry has enjoyed for decades.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us