Western Europe’s common disavowal of its Christian roots is usually less animated by antagonism and more than by an impression that religion is, in Christian Smith’s term, “obsolete.”

However, in Spain there has been within living memory a vicious civil war with major religious currents. The creeds of that war are still contested and may be coming to a head in disputes over one of the country’s major historical and religious sites, the Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen).

Despite Spain’s powerful and often aggressive secularist movements, the Catholic church still retains a somewhat privileged legal position. While the law states that no religion shall have a “state character,” Spain has a concordat with the Holy See. The 1953 concordat was amended in 1976 and 1979 to accord with the 1978 Constitution that established Spain as a non-denominational state.

The Constitution also states that “public authorities shall take into account the religious beliefs of Spanish society and consequently maintain appropriate cooperative relations with the Catholic Church and other denominations.” Catholicism is the only religious group explicitly mentioned in the Constitution and is the only religious entity to which people may allocate a percentage of their taxes, which about one third of Spaniards do.

However, already in 1973, under Franco, the Spanish Episcopal Conference had publicly declared its “willingness to renounce any privilege granted by the State in favor of ecclesiastical persons or entities….”

A week after Franco’s death in 1975, with the coronation of King Juan Carlos I, Cardinal Tarancón, a leading figure in the church, declared that the church needed to be detached from its history with the Franco regime, since the Second Vatican Council had taught that the “message of Christ… does not sponsor or impose any specific model of society.”

Meanwhile, the governmental Pluralism and Coexistence Coalition (FPC) promotes religious freedom and provides funds to non-Catholic religious groups having an agreement with the government to support cultural, educational, and social integration.

Notwithstanding these amicable arrangements, there is increased anti-Christian animus.

The 2024 Spanish Observatory for Religious Freedom Report found a sharp rise in anti-Christian hate crimes, with violent attacks, including the murder of a Catholic monk, doubling from the previous year. Vandalism of churches and symbols had increased by 12%. Christians were the main victims of religious freedom restrictions, suffering 168 of the 243 documented incidents. In previous years, about 85% of violations of religious freedom had targeted Catholics. In August 2025, there were seven cases of vandalism and desecration against Catholic churches.

Of the priests surveyed, 67% reported that they had experienced insults, mockery, or offensive remarks, 12% that they had been denied services or faced direct discrimination, and 15% that they had been excluded from meetings or events due to their clerical status.

90%

There are also legal restrictions. In November 2024, the Constitutional Court ruled against the male-only religious brotherhood Real y Venerable Esclavitud del Santísimo Cristo de La Laguna for refusing to admit a woman as a member, claiming that its internal statutes violate the Constitution.

In January 2025, following a complaint by the Spanish Association Against Conversion Therapies, the Ministry of Equality began an investigation of seven Catholic diocesesover alleged breaches of the 2023 Trans Equality Law. This vague law criminalizes action “aimed at modifying the sexual orientation or gender identity or expression of individuals, even with their consent.”

One incident recalls the civil war. On July 21, 2022, a Catholic priest received a letter containing death threats and the warning “You will burn like in ’36,” referring to the 1936 outbreak of war when thousands of priests, monks and nuns were assassinated, and churches destroyed.

In October 2024, a memorial cross in Neda, on one of the famed Camino de Santiago routes, was dismantled under Spain’s Law of Democratic Memory, which mandates the removal of Francoist symbols. The law requires only the removal of political plaques, but some municipalities have taken down entire crosses despite a court ruling that removing crosses stripped of political meaning was unjustified.

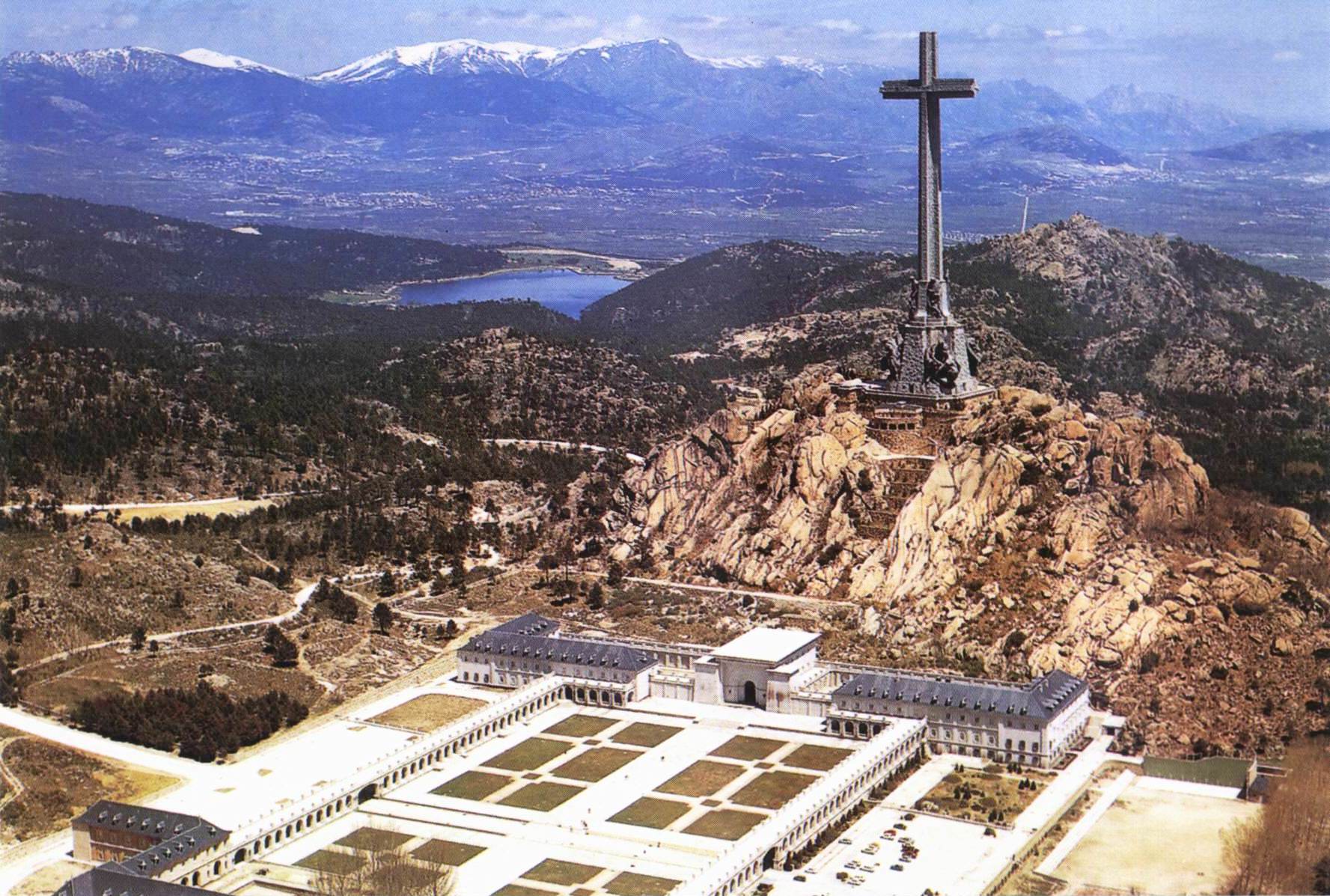

What is causing most controversy is changes to the Valle de Cuelgamuros, also called the Valle de los Caídos, the Valley of the Fallen. This massive memorial is dedicated to those, on both sides, who lost their lives during the 1936-1939 civil war. It was constructed by order of Franco and completed in 1958. Franco himself said that that it was intended as a “national act of atonement” and reconciliation. He was buried there in November 1975 but was exhumed in 2019 as part of an effort to erase all public homage to his dictatorship.

It is also a major religious site, containing a basilica, one of the largest in the world, the remains of thirty thousand war dead, an active Benedictine community, and what is probably the world’s largest Christian cross, visible from 20 miles away.

The Spanish government of Spain, led by the Socialist Workers’ Party under Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, wants to further secularize the memorial.

According to a November 17, 2025, report by the conservative American First Policy Institute, a proposed government project will “create a ‘great crack,”\’ a horizontal rupture across the Valley’s esplanade, designed to transform the site into a “space of dialogue and plurality.” It would also “eliminate the staircase leading to the Basilica and replace it with a large lobby containing an ‘interpretation center’ whose goal is to reframe the Valley’s meaning.”

The “pilgrim hostel, and even basic visitor access to the foot of the Cross and the Via Crucis (Stations of the Cross) have been progressively shut down, steadily limiting the site’s religious and cultural life. The Benedictine Prior, Fr. Santiago Cantera… was effectively forced out by the Sanchez government and replaced with a figure more aligned with the government’s vision.”

Since the monument is a Spanish state site, the government has flexibility in reshaping it and so this is probably not a religious freedom issue.

It is also understandable that the Spanish government is leery of seeming to celebrate a 36-year dictatorship. However, the proposed changes seem punitive in character and may create an architectural travesty.

It is also part of a common pattern to excise history so that we live only in an eternal present whose monuments merely mirror our current attitudes.